The maxim “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it” (often misattributed to Peter Drucker) sums up the continued belief in the necessity and power of accountability. A lack of accountability is seen as a sure path to lawlessness, indolence, and corruption. We don’t trust people who are unwilling, unprepared, or otherwise unable to render an account.

As a high school language arts teacher who is increasingly “going gradeless” in his teaching practice, I find that I am often left with few “measures” of student learning and growth. In its place, we have a lot of feedback — mostly verbal — and not the kind that fits easily (or at all, really) within the neat grids of a traditional gradebook. Although I still give the occasional quiz (always with the option to retake), this approach has largely disrupted the traditional economy of completing assignments in exchange for points. Since I am required to submit a grade at the end of each term, I involve students, using a Descriptive Grading Criteria to bring a modicum of consistency and fairness to this process. Students use a linked letter, screencast, or face-to-face conference with me to highlight evidence in their online portfolio supporting the letter grade they think they’ve earned.

But if I can’t measure it, how do I manage it? How can I hold my students accountable? And how can I, in turn, render an account to those above me?

To some degree, I’ve found workable answers to these questions. But I’d like to consider another question: What exactly does it mean to be accountable?

Following the etymological breadcrumbs, we know the word originates in the act of adding, enumerating, summing up. The prefix a– means we must convey this sum to another, presumably someone who has a stake in the result. And -able means that we are capable of performing both these tasks.

Before its emergence in Old French, the word seems to have leapt from the Latin verb computare, meaning “to count, sum up, reckon together.” That word derives its meaning from the prefix com- meaning “with” and the verb putare, “to reckon.” Before taking on this more modern meaning, putare meant “to prune,” and before that, “to strike, cut, stamp,” finding a common ancestor with more aggressive, violent words like dispute and amputate.

It’s not hard to imagine why ancient accounting might have involved this kind of violence. Transactions likely involved cutting off the correct amount of commodity or currency; authentication of an agreed-upon amount may have involved stamping with a seal or signet. And the fact that we did this cutting and stamping together may betray our deep-set fear of getting duped.

Returning to the present, accountability continues to represent an interesting combination of contention and consensus. Even today, the ambivalence and unease it occasions seems to flow from its ancient origin: the act of impressing symbolic agreement, certainty, and exactitude on something fundamentally malleable, arbitrary, and uncertain. Although its usage has strayed far beyond these origins, accountability still makes the most sense when it involves a transaction, what educational philosopher Gert Biesta describes as “an exchange between a provider and a consumer.”

The fluidity and nuance of education makes us especially uneasy because it isn’t easily summed up, certified, or commodified. And when so much money is involved, it’s easy to see why people might think they’re getting swindled. Thus, schools, administrators, teachers, and students must find ways to produce measurable results. Even in making the case for going gradeless, I often find myself arguing from the standpoint of how that change will show up in measurable ways. Research has shown how, by forgoing grades during the formative period (and, in the process, not measuring or certifying learning), we can produce even greater gains. Greater gains on what? On the eventual summative assessment, usually the state, national, or international exam.

In other words, even without the daily currency of grades, I can still pay up come test time. All I’ve done is write you an IOU for an even more impressive amount. At that point have I really escaped the transactional nature of this paradigm?

I’m not saying it’s wrong for us to want the most “bang for our buck” from schools. What I am saying is that accountability—with its impulse to strike, to cut, to stamp—has often resulted in us getting far less than we bargained for.

By its very nature, accountability limits our focus to that which can be counted, ignoring the existence of anything unmeasurable or subjective. This fact is perhaps most evident in the humanities, where learning to grapple with complex, interconnected, irreducible realities is of central importance. As Bill Ferriter asserts, “The truth is that the things that are the most meaningful are also the hardest to measure.”

Instead, we choose the lesser part, crowding our curriculum with things that are most measurable, things which are, not coincidentally, least meaningful. Accountability pressures us to eviscerate the disciplines we love, turning them into stale collections of discrete, demonstrable steps and concepts unmoored from their central essence.

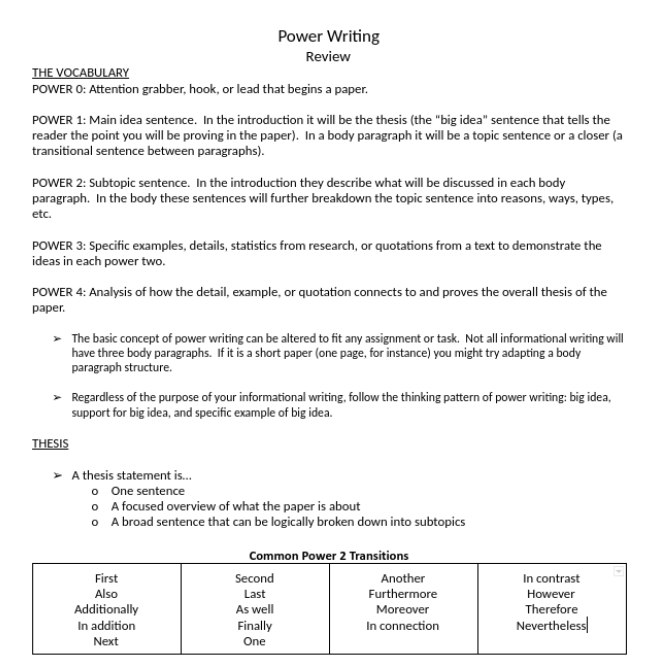

Perhaps the most obvious victim of this approach is writing, a discipline which, as Linda Mabry observes, is “fundamentally self-expressive and individualistic.” In order to enact the alchemy of making writing measurable, we must narrow our field of vision to contain “only a sliver of…values about writing: voice, wording, sentence fluency, conventions, content, organization, and presentation.” Often, this attempt to render writing accountable is paired with a prescriptive form or template.

As Paul Thomas puts it,

…the root of what my students do not know and often badly misunderstand is the template used to teach students in most K-12 settings. Further, I now believe that teachers using those templates are also misled about their students’ concepts of sentence formation, paragraphs, and essays because the template and prescriptions mask the lack of understanding…Rules and prescriptions, I am convinced, impede the development of conceptual understanding of how and why to form sentences and paragraphs in order to achieve an essay.

Author and writing professor John Warner points out how this kind of accountability, standardization, and routinization short-circuits students’ pursuit of forms “defined by the rhetorical situation” and values “rooted in audience needs.”

What we are measuring when we are accountable, then, is something other than the core values of writing. Ironically, the very act of accounting for student progress in writing almost guarantees that we will receive only a poor counterfeit, one emptied of its essence.

Some might say that accountability only makes a modest claim on teaching, that nothing prevents teachers from going beyond its measurable minimum toward higher values of critical thinking, problem solving, and creativity. Many seem to think that scoring high on lower-order assessments still serves as a proxy for higher-order skills.

More often than not, however, the test becomes the target. And as Goodhart’s law (phrased here by Mary Strathern) asserts, “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” What we end up aiming at, in other words, is something other than the thing we wanted to improve or demonstrate. When push comes to shove in public schools — and push almost always comes to shove — it’s the test, the measure, the moment of reckoning we attend to.

For most of my career, I’ve seen how a culture of accountability has caused the focus of administrators, teachers, and students to solidify around the narrow prescriptions and algorithmic thinking found on most tests. When that happens, the measure no longer represents anything higher order. Instead, we demonstrate our ability to fill the template, follow the algorithm, jump through the hoop. And unfortunately, as many students find out too late, success on the test does not guarantee that one has developed the skills or dispositions needed in any real field. In fact, students who succeed in this arena may be even more oblivious to the absence of these.

Approaches that show how eschewing grades in the formative period can lead to greater gains on standardized exams still run a constant risk of narrowing their focus to serve prescriptive, sterile ends. How many teachers and students can bravely embrace what John Updike called “that strange law whereby, like Orpheus leading Eurydice, we achieve our desire by turning our back on it”? How many of us, when the stakes are high enough, will instead lose nerve and falter before guiding students back to the sunlit regions of discovery and growth?

And how can we lead them, when we ourselves are condemned to this same Sisyphean fate, squirreling away points in order to avoid the poor evaluation score? Often any creativity, critical thinking, or problem solving I’ve brought to my own teaching has been at my own peril. Taking risks, trying new strategies, questioning long-accepted norms almost always involves an unacceptable implementation dip. It’s safer to get with the program: post your learning objectives; manage your transitions; model, practice, and routinize your procedures.

WWDD: What would Danielson do?

The abused becomes the abuser. Dehumanizing demands for accountability will continue until someone stands up and stops it. In my experience, that stand largely falls to teachers, those with the courage to carve out human spaces within a pervasive milieu of mistrust and measurement. A first step for many of us is reining in our own compulsion to manage through measurement, using grades as behavioral carrots and sticks.

And again,

Without the currency of numbers, we glimpse anew the immeasurable value of the students in our care and the potential of our time together. We don’t need to capture or quantify these unmeasurables to appreciate or cultivate them. We don’t need to add, enumerate, or sum anything up for learning and growth to occur. In fact, we may find that the old impulse to strike, to cut, to stamp is antithetical to teaching and learning.

As Peter Drucker (actually) said,

Your first role . . . is the personal one. It is the relationship with people, the development of mutual confidence, the identification of people, the creation of a community. This is something only you can do…It cannot be measured or easily defined. But it is not only a key function. It is one only you can perform.

What will it take for us to start thinking of accountability, not as a numerical concern, but as a responsiveness to the students in our care, a reciprocity that cannot be mediated by measurement?

This article also appeared in the Journal of School & Society, Volume 4, Issue 2.

Again, you hit the nail on the head. As I am grading finals and assessing work, I found myself asking this very question…why am I putting a grade into the computer when what these kids have done really should not be debased by a number? In many cases the students put their hearts and minds into the take home portions of the ‘final’ and when they didn’t, their self-assessment reflected the holes. Given the opportunity to improve, I suspect that many would take their submissions back in order to “do better now that I understand better what it should look like.” Unfortunately, as I write this, I am also certain that many students are watching their grades fluctuate like the stock market tickers as we teachers input, update and change grades on the LMS. UGGGH. Keep up the good fight Arthur.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks, Dan. “Debased” is a good word for it. And the notion of “watching the stock market” captures how so much of this feels totally out of their hands, just something that fluctuates in idiosyncratic ways from class to class.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on danthescienceman and commented:

Teaching will never be measurable in the sense of “accounting”. It is an art as much as a science and the more we attempt to quantify it, the less likely we are to allow teachers to practice the art of it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This resonated with me: “Although I still give the occasional quiz (always with the option to retake), this approach has largely disrupted the traditional economy of completing assignments in exchange for points.”

Your use of the word “economy” is entirely accurate and something I’d forgotten. Several years ago I attended a workshop at Bard College’s Institute for Writing and Thinking entitled “Why Write?” The text we studied Lewis Hyde’s “The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World.” I was teaching a middle school humanities course at the time, a curriculum I had largely self-created. I applied notions of Hyde’s use of the “Gift Economy” to my teaching then, and I still apply it now in High School. Here are my imperfect musings on that experience/concept: https://coopcatalyst.wordpress.com/2012/09/23/albert-einstein-lewis-hyde-and-the-gifts-of-teaching/

However, at the time I was not “gradeless” because I didn’t see a pathway to such an existence. Your work, Arthur, as well as all those here at Teachersgoinggradeless.com has helped me navigate myself to clearer waters.

Thank you for continuously sharing your own journey.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Thank you, Garreth. Wow, these are some advanced reflections. I think I was just coming out of the Stone Age in 2012. What I so appreciate is the power of metaphor to simultaneously disrupt the dominant one and provide a viable alternative. Thinking in terms of education as “gift” is so helpful, especially as we are coming into this season of giving. Rather than a cashier “proving out” a cash register at the end of the shift as accountability, how about focusing on giving good gifts to our students? And better, imagining school as an opportunity to exchange good gifts, appreciating those gifts, and finding ways to acknowledge/say thank you for those gifts. (As an aside, I’d love you to write us something on this economy of giving! 😉).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on Only Connect and commented:

The insight and understanding here should keep you coming back. Gradelessness isn’t about disruption so much as it’s a massive course correction in a more humane direction.

LikeLiked by 3 people

There is so much in this essay to go think on, Arthur. As I was reading about the template for writing, I thought – “What if my blog posts were evaluated against that kind of criteria? What if, instead of heartfelt comments people left a string of numbers in boxes referring to this disembodied elements of my writing attempt?” I doubt seriously that I would keep writing. Thank you for going deeper into the origins of this term to which we as an industry (and we are increasingly precisely that) pay great heed. Your writing is often both informative and clarifying for me, I always learn something new – often about myself and my beliefs.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Goodness no, Sherri! I’m sure your posts would measure up on any old rubric, but would the criteria fully appreciate the way you invite us meander with you, the way I walk away feeling both challenged and listened to? Hard to quantify that! And yet, I’m not sure I could live without that kind of writing in my life. I just wonder how many writers we alienate in the interest of eking out what’s merely acceptable.

This isn’t to say there isn’t room for improvement or growth. That has been a lifelong struggle. But how does that happen for us as writers? Mostly through being readers, by “apprenticing” ourselves to the writers we most admire, by learning to grapple with ideas and connections through writing. I’m not great at facilitating this experience as a teacher, but I feel these prescriptive approaches hinder more than help. Thanks as always for your thoughts!

LikeLike

Many thanks for the unexpected Christmas present here Arthur – it is always great to read something new from you.

As an administrator, I live in a dunk tank of accountability – everytime you think that you have reported on everything you were supposed to another ball whacks the target and you get submerged again. It wouldn’t be so bad if most of those things were related to kids or teaching, but sadly that is not the case.

I take your point about the etymology of ‘accountability’, and I think we have spoken before about the language of business and commerce (and sadly competition and violence) being somehow central to the lexicon of education. This needs to change. Words shape our reality and in teaching define our practice. We cannot hope to create something that opens new possibilities or transforms our pedagogy unless we abandon this language for something new.

I will put it to you again, as I have before – what language, images, or motifs offer a way out of this discourse into a place that cherishes equity, difference, individual choices, personal expression, and wonder? I believe that it isn’t enough to talk about equity, for example, and that we instead must create talk that embodies equity – if that makes any sense.

One of the things I have discovered in my time in leadership is that shared languages are powerful. When you can get people talking the same ways, you align practice and action in ways that make change ripple and amplify and transform spaces and cultures.

So let’s start with one word – the word you highlight here – accountability. If it will not suffice then what will? Obligation, duty, responsibility? Certainly, I think, our relationship with students requires something to recognize the connection and expectation.

I know what word I would use, but I think the value in this kind of exercise is imagining what the positive and negative impacts of the words we choose are – from the outset, and creating a vision in collaboration with others. If we are to develop a culture that does not ultimately look to the test for validation, this is work we need to do.

As always, thanks for sharing your ideas. You are an educator I admire greatly.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Mark,

If I ever leave this country, it will be to come work for you up in Canada.

I agree with you about the need for new language. I feel it’s all about the kind of looking and knowing that we do. Even after enduring multiple humiliations, the heirs of empiricism still believe in its unrivaled ability to put us in direct contact with the truth of things. Standards-based approaches have tried to restore credibility to this lens by removing the ways it has been misused as an instrument of compliance. But some recent reading is making me think that the impulse to measure is, in its essence, an imposing of sovereignty on the other, a relegation of the other to the status of absolute object. In other words, there’s no good way to do this, at least not as the central function of schools.

What’s the alternative? Not sure, but I guess the word I’m beginning to settle on is “recognition.” And if I can have another word, I’d like to have “mutual recognition.” As a teacher, I need to be recognized by you. You won’t recognize me through the lens of Danielson. How do you recognize me? Not sure, but I’m increasingly convinced that you must, and that Danielson will make it harder if not impossible for you to do so.

Measuring is automatically “I-it”; recognition is “I-Thou.” What makes school sometimes feel so awful is the continual experience of objectification, which we continue to impose on one another in various forms. Yes, there are forces arrayed against us, but there’s also a place for leadership, for someone who can pave the way for this paradigm amid near-constant opposition.

Cue Matthew 11:12:

“From the days of John the Baptist until now, the kingdom of heaven suffers violence, and the violent are taking it by force.”

Happy Advent, friend.

LikeLike

The Buber reference is spot on! I used to take classes from a woman in Philadelphia who created her own “institute”, the “Lena Allen-Shore Institute.” She was a Holocaust survivor, had a masters degree from McGill, and had met Pope John Paul II several times in personal meetings. An amazing lady, she taught me more about people and the real work of a teacher than most of my college classes combined. It was she who introduced me to the work of Buber. I couldn’t be more in agreement with how you’ve applied his terms here.

Years later I wrote an essay for a publication of Bard College’s Institute for Writing and Thinking in which I used Buber’s distinction between experience and encounter to describe the magic of being immersed in a book. I marvel now, thinking about what you’ve written above, that I didn’t take that connection further and recognize the same “deep encounter” I found in reading is actually my goal as a teacher.

These kinds of exchanges teach me so much about craft. I’m utterly appreciative of the work of everyone here. Thank you.

(If you’re interested in the paper with the Buber reference, it’s here: https://www.academia.edu/5013560/Touching_the_Sturgeon )

LikeLiked by 1 person

I woke up this morning not with one word ringing in my head, but three. Three powerful words that light my way and guide my thinking. It could be that one of these words is more powerful than the others. It could be that I should focus on my “one true thing.”

But I am not ready to do that yet and am certainly not convinced that I should. Because these words, these ideas, these guiding principles…they go together. They reinforce each other. They inform each other. They balance each other.

And the words are….

“Owned”

I have stepped foot in too many classrooms and districts where no-one really seemed to own the learning–not the students, not the teachers, not the administrators and not even the districts. All of these “stakeholders” may have been working really hard to do what they thought they needed to do, but they weren’t owning it. They were trying to make the grade, meet the standard, hit the target, obey the laws, fulfill the mandate.

Ownership is something very different than that.

Ownership says, “This is my learning. I have a say. I get to design it. I get to create it. I get to take responsibility for it. I get to experiment with it. I get to explore it.”

And ownership will only come when we move away from mandates and high stakes and forced compliance.

“Nuanced”

Too often in education we operate in binaries and focus on implementation. We rush to define best practice and think in terms of this not that. “Learning should be deep not shallow.” “It should be experiential not rote.” “We should teach phonics not whole language.” “Or whole language not phonics.”

Richard F. Elmore says,

“I currently live in a world in which I routinely watch well-intentioned, highly motivated educators–teachers and administrators–talk obsessively about “best practice” as it it were a kind of super-hero jumpsuit you could slip on before you step into your formal role as “change agent.” I am routinely asked by well-meaning system-level leaders to talk to groups of more than 100 teachers and administrators about deeply complex practices of leadership and instructional practice that can only be learned through deep, daily immersion in guided practice.

“Implementation” is something you do when you already know what to do; “learning” is something you do when you don’t yet know what to do. The casual way policy-focused people use the term obscures this critical distinction. The knowledge of what to do has to reside not in the mind of some distant policy wonk or academic, but in the deep muscle-memory of the actual doer. When we are asking teachers and school leaders to do things they don’t (yet) know how to do, we are not asking them to “implement” something, we are asking them to learn, think, and form their identities in different ways. We are, in short, asking them to be different people.”

Let us not look for binaries, but instead immerse ourselves in the science and study of learning and look for what works in this setting at this this time with this team and these learners.

“Fluid”

Water is so powerful that it shapes itself to whatever environment it finds itself in and at the same time can radically alter that environment.

I want us to create schools and systems that can do the same thing. Schools where there is no one solution or one strategy or one system. Schools with schedules that are flexible and the pathways to learning can be adjusted as needed instead of at the next semester or next school year.

Learners do not all start at the same place and learn at the same rate. Expecting everyone to do so causes a huge amount of psychological damage and yet almost every school I have ever worked with is based upon a system that expects that from learners.

We need to create systems that are more fluid. Where learners can craft multiple paths to mastery and not feel shame if their path looks different from others. I personally haven’t seen any of these systems in real life, but I know that they are out there and that more and more educators are leading the way in crafting learning environments that go beyond “differentiation” and “personalization” to becoming truly adaptive and fluid.

So those are my three aspirational words that I hope can help guide our “discourse into a place that cherishes individual equity, differences, individual choices, personal expression, and wonder.”

I am standing for learning that is owned, nuanced, and fluid.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Perfectly said. Thank you.

LikeLike

Mark, thank you for the response from “the other side”. As a classroom teacher I could not agree with you more. Words and thus the lexicon of pedagogy is akin to dialects. If we, teachers, students, administrators and counselors…okay, parents too…could use the same language, it seems we would be more closely aligned in our goals and outcomes. It would also be helpful of the colleges could join us. Often it seems that colleges want us to prepare our students for success, but with so many of our practices aligned with tests and grades, we can not necessarily accomplish it. We want our students to be so much more; to do so much more. Dare I say to own more of their learning. But then we HAVE to test and grade and align, etc. How do we move to unifying the language such that we are all speaking the same dialect? Am I making sense?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Garreth,

I think we’re definitely trying to land the same fish! Love the article. I would agree that our experiences in the humanities and literature make us sensitive to the way we can dispel the magic of “deep encounter.” Your paper called to mind Thomas Merton’s likening encounters with the “true self” to encountering the “shy wild deer” around Gethsemani. The slightest wrong move will send that skittish deer running. Here’s a good essay on Merton’s use of that metaphor: http://merton.org/ITMS/Annual/4/Kilcourse97-109.pdf

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: December 2017 Edition: What’s News In Education? - Maths Pathway

Pingback: Five Words to Shape Our Learning Reality – A View from the Curve

Pingback: Thinking about teaching – Inherit and Respond

Pingback: Education Evolutions #48 | Haas | Learning